|

Vol. 1, Issue #24 Dec. 22nd - Jan. 4th, 2006

The Voynich Manuscript

The manuscripts first recorded account in history comes from Prague while Emperor Rudolf II reigned during the Holy Roman Bohemian era. The Voynich Manuscript was given to Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenec from the emperor in hopes of decoding it’s message. It’s unclear if Jacobus Horcicky originally sold the manuscript, or just obtained to book to study on the emperors behalf- but both theories remain open ended. Jacobus Horcicky gained full ownership of the strange book when the emperor died in 1612 and it’s believed the book, along with the rest of his possessions, fell into Jesuit hands sometime after 1619. Since that time, the book fell into the lap of a mysterious owner. When William Voynich discovered the book in 1912, he found Johannes Marcus Marci’s Letter, a short correspondence between him and Athanasius Kircher- Marci’s bohemian contemporary. The letter conveyed that Marci was waiting on inheriting the book from an intimate friend. The two men communicated about the manuscript for 25 years. The letter found by Voynich was the last of a long correspondence between Johannes Marcus Marci and Athanasius Kircher. Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenec’s signature was scribed on the letter, probably relating to the older owner. Athanasius Kircher was an established scientist and mathematician. Over 2000 letters are still on record from his pen, written to and from popes, emperors and people like Marci. 35 - 36 of these letters between Marci and Kircher were preserved at the Pontificia Università Gregoriana in a volume labeled ‘From the private library of P. Beckx’. Voynich discovered these letters and one in particular written by a M.Georgius Baresch, clearing up who the mysterious owner was. According to some of the letters, Baresch had sent Marci and Kircher several transcriptions of the manuscript to study for years. Marci gained possession of the book before 1662 and held it for a few years before his death in 1666, (the date noted from the letter discovered inside the book’s cover during Voynich’s 19th century studies. ) After Marci’s death, Kircher probably held the manuscript for a long time, but after this owner the book disappears into obscurity. Most likely the manuscript was pulled around museums and scholars until 1773 but stayed in Jesuit control until Vittorio Emanuele captured Rome in 1870, confiscated the books held there. The Jesuits were given slack though, to maintain morale among the Catholic populace during occupation, and the ‘Private library of P. Beckx’ was saved.

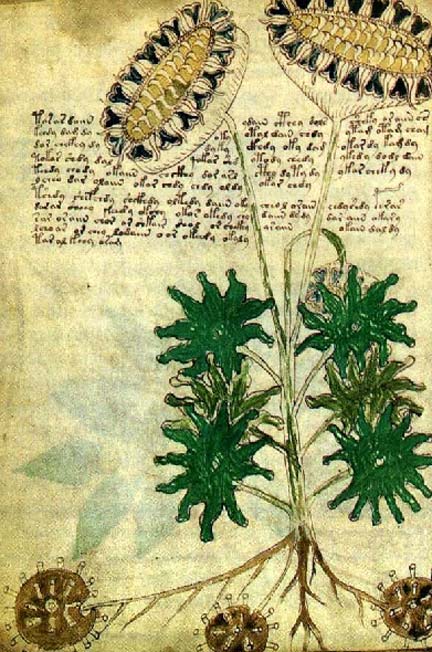

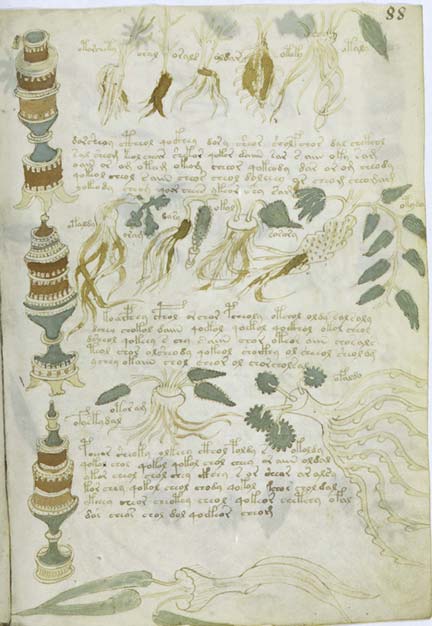

The manuscript itself is fitted with celestial illustrations depicting strange plants, congregations of naked men and women, and colorful circular calendars. Some believe they book contains herbal remedies, but since the plants shown in the book are not found anywhere on earth, this theory is somewhat unlikely. Others think the book is an encrypted language from God called Enochian, an angelic codex written by the biblical figure Methuselah after a guided tour through the heavens. After failed attempts to decipher a single word by both American and British experts, another theory has developed dismissing the book as an elaborate hoax. This, too, is unlikely considering the precise reoccurring symbols and rudiments in the text. Other methods by cryptologists have included decoding the text as an algorithm, or characters meant to be seen as numbers. Another idea was tried by James Fin. His book, Pandora’s Hope, released in 2004, contested that the code was a visual cypher put into Hebrew. This was plausible, considering the repeating characters AIN (shown in the manuscript in the variants AIIN and AIIIN), the Hebrew word for ‘eye’. The complex and unpredictable pattern in the manuscript clashes with this theory though, offering no other viable translations. The linguist Jacques Guy probably came to the nearest solution by suggesting the characters and symbolic images in the book deeply resembled the Tai and Chinese language. Guy believe the language was a kind of phonetic translation by a westerner, or possibly, an eastern native scribing his/her verbal language onto paper. Others have said the text is a kind of free flowing language brought to the writer in a trance. In this theory, the manuscript works as a guide into the afterlife and a means to gain health and prosperity. On the darker end, following the grimoire motif, the Voynich book is a spellbook dictating curses, satanic ceremonies and group condoned suicides. The Voynich Manuscript is currently housed in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University in Connecticut. It still remains an ancient uncracked body of work that has frustrated innumberable cryptologists and scholars, sometimes to their bitter ends. The manuscript has since appeared in Colin Wilson’s 1969 short story The Return of the Lloigor and Brad Strickland’s The Wrath of the Grinning Ghost. Even video games like Broken Sword and Radiata Stories have implented the age old mystery into their plots for added allure. Still, the book remains a largely forgotten cult mystery and will likely remain that way until someone proves it otherwise. |

||

©2006 NONCO Media, L.L.C.

The strange document was officially discovered in 1921 and named after it’s popular founder, William M. Voynich. Since its first appearance in 1586, cryptologists and codebreakers have tried in droves to decipher the text but after four centuries the book remains “The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World”. Everything about the document is impossible to translate. The author is unknown, along with the book’s origin and the font cannot be accurately compared to any other language on the planet.

The strange document was officially discovered in 1921 and named after it’s popular founder, William M. Voynich. Since its first appearance in 1586, cryptologists and codebreakers have tried in droves to decipher the text but after four centuries the book remains “The Most Mysterious Manuscript in the World”. Everything about the document is impossible to translate. The author is unknown, along with the book’s origin and the font cannot be accurately compared to any other language on the planet. A little time later William Voynich was brought to visit the Villa Mondragone, a Jesuit boarding school. In financial straights the Jesuits had to sell 1000 manuscripts and Voynich bought some 30 books, including the strange book he later dubbed after his own name.

A little time later William Voynich was brought to visit the Villa Mondragone, a Jesuit boarding school. In financial straights the Jesuits had to sell 1000 manuscripts and Voynich bought some 30 books, including the strange book he later dubbed after his own name.