|

Vol. 1, Issue #22 Nov. 24th - Dec. 7th, 2006

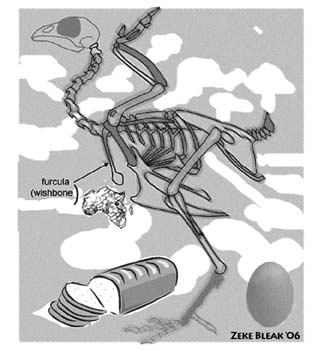

The Sublime, the Absurd, & the Tragic

Most of the vendors are women, hunkered behind fat cloth sacks exuding powdered elixir, their dark eyes peering expectantly up from under tired muslin scarves. Each has displayed samplings of spices in hand-woven baskets lined neatly across weathered planks. The huge market is crisscrossed with a complex maze of rabbit run paths and trails, twisting and turning, sometimes coming to an abrupt dead end. There are thousands of sellers, and as I walk along, overwhelmed, I wonder how any of them can make a living. The sprawling district also sells grains, fruits and vegetables, hundreds of coffee varieties, goats, lamb and handicrafts. The air is filled with a fine mist of spices floating on the breeze, and the red-brown smoke is not smog, but a haze of exotic blended spices hovering over my head. I find myself euphoric, and I realize I am actually “high” from absorbing and inhaling the pungent cloud of nutmeg, peppers, cinnamon, turmeric, cloves, ginger, curry, and garlic. Finally I stand before one especially colorful tent, ready to buy, before I remember bringing foodstuff back to the United States is not permitted. So I decline the proffered herbs and mostly out of guilt, I buy several silver Coptic crosses, and tell myself I’ll give them to my wife for Christmas. • The next day we head out of the huge capital city of Addis Ababa, over five million strong, in a lumbering green Land Rover, poised for a ten-hour gut-jarring ride over dangerous desert terrain. We know ruthless bandits hide in the countryside, waiting to assault and rob wayfarers. In most Third World counties any American is considered wealthy, and by their standards, it’s probably true. Just before we leave the crowded city, we stop behind an ugly American-made car, and someone notices on the back written in chrome script is: Bob Moore Cadillac, Oklahoma City! We all laugh at the absurd coincidence--a car sold in Oklahoma City, our town, stopped in front of us in a huge African city. We surmise an oil executive, probably with Halliburton, was stationed somewhere in North Africa in the Seventies, and had his favorite car shipped for his pleasure. It reminded me of the first time I traveled to Africa and landed in Kenya. Soon after I went to the rooftop bar of my Nairobi hotel for a drink, and walked in as a band from Texas was cranking out Proud Mary--a bad rendition as an added insult. • In the slow but reliable Land Rover, we descend from the high Addis Ababa plateau (8,000 feet) and wind down narrow roads through beautiful, exotic eucalyptus forests and over impeccable stone bridges and tunnels engineered by the Italians during World War Two. The Italians occupied the country during the war. Hours later we pull into a sprawling dusty tent camp on the edge of Bati, a small village of less than 12,000 on the vast desert floor of Ethiopia. A drought that has lasted for a decade has driven an estimated 30,000 to this region, and as we learned, most of them would die of starvation or diseases related to prolonged malnutrition. Most were poor subsistent farmers who had waited too long to leave their mud huts and tents to seek food and aid. They waited and waited, hoping the next year, or the next month, or the next day would bring drought-busting rainfall. It never happened. Whole families lay dying in the dust, some in tents, others literally sprawled without shelter or even a blanket on the hard-packed alkaline dirt of northern Ethiopia. Everywhere children with each skeletal bone clearly etched through paper-thin skin sat on their spare haunches and slowly rocked in physical and psychic pain and often retched and followed us with their luminous gaze, their eyes made large by their drawn and dehydrated skin. I saw some in the morning, their eyes glazed with pain, only to see them later in the afternoon, as corpses, lovingly washed and wrapped with eucalyptus leaves and clean muslin and stacked in the corner of the death hut, like loaves of bread, awaiting the gravediggers’ incessant march up the hill for interment in the hard, rocky bowels of Africa. This tragic ritual continued from daybreak to dusk, day after day. As I wandered the camp documenting this human tragedy, I literally felt my energy being drained from my body. After only three hours of work, I was exhausted. Others in my entourage made a similar testimony. We felt the sick and dying were unconsciously sucking our energy in an effort to survive. It was heart-breaking to witness such suffering, especially in children. By the time we arrived, much food had arrived from around the world---I saw the flags of Japan, Sweden, Germany and the United States stamped on sacks of grain. But, it was too late. Their bodies were too weak to accept food and the diseases had too firm a grip on their fragile organs. On the second day our little group from Oklahoma gathered for lunch in a tin shed near the camp. We each had a piece of bread and a hard-boiled egg, a meager meal, considering the heat and the strain on our bodies. Someone observed that today was our Thanksgiving Day back in America. At first we exchanged ironic chuckles and comments, but as we ate our dry, spare meal, we grew silent, and thought of those dying on the desert floor, and we gave thanks for our bread and egg, and were, for the first time in our lives, truly thankful on Thanksgiving. |

||

©2006 NONCO Media, L.L.C.

The world’s largest open-air spice market is the Mercado in Addis Ababa. It stretches on for what seems like miles—tent after makeshift tent, stall after stall—one ramshackle cubicle after another brimming with every spice and herb known to man. I’m in Ethiopia to document the massive famine that grips the remote desert regions of the country, traveling with the Oklahoma City-based relief organization Feed The Children.

The world’s largest open-air spice market is the Mercado in Addis Ababa. It stretches on for what seems like miles—tent after makeshift tent, stall after stall—one ramshackle cubicle after another brimming with every spice and herb known to man. I’m in Ethiopia to document the massive famine that grips the remote desert regions of the country, traveling with the Oklahoma City-based relief organization Feed The Children.